There’s no doubt that the legacy of ideology and political culture weighs heavily on the decisions of political leaderships everywhere, particularly in China where its antecedents and institutions are so deeply entrenched. But the huge changes and problems that China and its leaders have to deal with at this point in the country’s history defy interpretation though a one-dimensional ideological lens. Why leaders and their advisers come up with particular policy platforms and prioritise certain strategies to deal with them warrants more detailed and careful analysis.

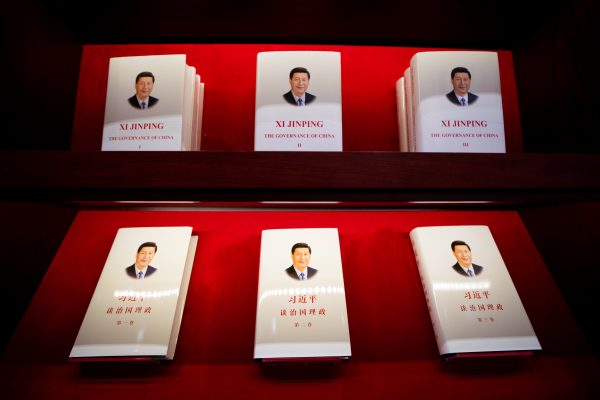

President Xi Jinping’s elevation of ‘common prosperity’ into a political campaign to secure his political future at the 20th Party Congress next year is a monumental case in point.

Is this ‘move to the left’ a reassertion of ‘the power of the Communist Party of China (CPC) as an institution over the policy, technocratic and administrative agencies of the Chinese state, as we have seen in the empowerment of the Party within state-owned enterprises and private firms as well as the return of Marxist-Leninist ideology as the organising principle for Chinese politics’ as some like former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd claim? Or are there other reasons that might explain where Xi and the Chinese leadership are headed?

The political debate in China that has erupted around this grand policy shift that seeks to rewrite the Chinese social contract around a political meme that dates back to Chairman Mao Zedong is certainly all over the ideological shop.

In the blogosphere, the relatively unknown Li Guangman cheered on the clampdowns on everything from internet companies, foreign-leaning film stars, tax dodgers, online gaming, tutoring and insufficiently masculine internet stars, and hailed common prosperity as the dawn of a new cultural revolution. His cry from the past even made it to the People’s Daily and the Global Times. Economists Zhang Weiying from Peking University’s National Development School, Zhang Jun, Dean of Economics at Fudan University, and Tsinghua University’s Li Daokui were among those who cautioned that to ‘lose faith in market forces and rely on frequent government intervention, (would) lead to common poverty’. They were joined somewhat surprisingly by Hu Xijing, editor at the Global Times and certainly no ‘capitalist roader’, who rejected the notion that anything remotely like a Cultural Revolution was on the cards, and proclaimed that Chinese reform and opening up are alive and well and that there would be no retreat from policies of the 18th National Congress of the CPC.

Deputy Premier Liu He added his weight to the view that the market and private entrepreneurs were central to China’s success. ‘The private sector contributes more than 50 per cent of the tax revenue, more than 60 per cent of the GDP, and over 70 per cent of the technological innovations’, Liu said. ‘It provides more than 80 per cent of urban employment and accounts for more than 90 per cent of market entities in China’.

But China has a widening income and wealth divide — the inheritance of decades of widely successful market-led growth. That’s created a middle class of 340 million people earning between US$15,000 and US$75,000 per year, a number projected to reach 500 million by 2025. In 2020, China also had an estimated 1,100 billionaires and 5.2 million millionaires, in US dollars. The wealthiest 1 per cent of Chinese held 30.6 per cent of the country’s wealth, up from 20.9 per cent two decades ago.

Meanwhile, Premier Li Keqiang pointed out last year, the nation had 600 million people living on a monthly income of 1,000 yuan (US$154), barely enough to cover monthly rent in a mid-sized Chinese city. The income Gini coefficient has hovered between 0.46 and 0.49 over the past two decades — a level of 0.40 is usually regarded as a red line for inequality. The wealth gap is even starker. The wealth Gini coefficient rose from 0.599 in 2000 to 0.704 in 2020 — an extreme that would seed social instability in most countries.

In our lead article this week Cai Fang suggests that the Chinese leadership’s reiteration of common prosperity as a principal policy goal is thus very timely.

‘It is a logical continuation of the long-term task of eliminating poverty and nurturing the low-income to the middle-income group’, Cai says. ‘There is need to tackle the challenges facing China’s economic development and social cohesion. The Chinese economy is increasingly constrained by weakening demand as its population rapidly ages. Growing the pie and dividing it more fairly is the key to increasing the contribution of household consumption to economic growth’. And policy strategies directed at addressing the equalities are common to international experience and common practice. ‘China’s real per capita GDP is predicted to increase from US$10,687 in 2020 to US$23,000 in 2035. In such a span of development, according to cross-national data, the average proportion of government expenditure to GDP increases from 26 per cent to 36 per cent’, Cai points out.

The market economy, it’s been made clear, plays the primary role in distributing wealth and income. After this, the government steps in to redistribute income and ensure the welfare of society as a whole. Finally, the well-off have a role to play through charity and social responsibility, shaping the culture of a supportive and inclusive community.

Xi Jinping, whatever else one may say about him, inherited a China that in many ways made the last four decades of 19th century America — with its robber barons, rampant corruption, gross inequalities and obscene concentrations of wealth — look like a picnic in the park. That was the so-called American Gilded Age, as James Kynge recalled in the Financial Times last month. A Progressive Era of sorts followed in the United States, though much more successfully in the European industrial states.

China needs its own Progressive Era today. It means a huge shake up in the regulation of markets and monopolies new and old, including in the state-owned enterprise sector. It means a massive revamp of the taxation and income transfer system where China lags behind the moderately rich societies it now seeks to emulate — and that won’t be easy. And it means entrenching a culture of social responsibility that has looked a little tattered for some time.

If that’s what the campaign for common prosperity is about, it’s a relevant, highly pragmatic and politically astute strategy to address the challenges that China now confronts. It aligns with the ideological stars but they only faintly provide its navigational bearings. It’s a campaign in which Xi will assuredly win the political race.

Delivering on the mandate, of course, is another matter altogether.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

China’s push toward “common prosperity” is not much different than Japan or even Norway, so this idea that you can’t have common prosperity and significant market-driven business activity at the same time is false.

I think it is the contrast it presents when compared to America’s hyper-inequality that alarms some commentators, which may be more of valid criticism of the American system than the Chinese. Obsessive focus and glorification of billionaires – those who hoard wealth – may not be the ideal system that works best for most of your citizens.

It would appear that America could learn quite a bit from China’s “common prosperity” to reduce its gross inequality that is undermining the quality of life and human happiness in the United States. Ayn Rand’s Galt’s Gulch, capitalist utopia really is a work of fiction, not a sustainable system that encourages commonality and connection between people.

Li Guangman versus Hu Xijing or arguments among prominent Beida-Tsinghua scholars are all battles among titans of Olympus. In my view, to say today’s China has (allows) diverse political positions is like saying Chairman Mao’s period also had diverse political positions, because titans of CCP then were making arguments. Reading too much into titans’ battles could mask changes in Chinese society. Taking a look at contents of Chinese newspapers, TV shows, netizens, talking with ordinal academics in ordinal Chinese universities, white collar workers, and one senses that Xi Jinping’s China is starkly a difference place from what it was 15 or 20 years ago. Apparently better off but much more tightly controlled.

This is a good article. My question is “Why would China now lean to its more “left leaning” post WWII political roots versus its clear market driven success and prosperity over the past two decades?”

My own thoughts are that its easier to manage a more centrally controlled/communistic economy versus a more diverse western-style market driven economy. Or maybe I should say “control” versus “manage?” The conspiracist in me would suggest that now that Chinese entrepreneurs have invested so much into building a booming economy, could it be a good time for the state to come in and “manage” these businesses in a more direct/centralized fashion? Its hard enough for purely market driven countries to plan economic direction in a hugely complex world. One can imagine the issues China faces as it embraces market driven prosperity with its traditional left leaning political foundations post WWII?

I believe this is the true dilemma China is in. Introducing market driven prosperity has inherently brought with it the need for wealth driven class divisions that the traditional Marxist government is struggling to deal with on a standardized basis. The easiest solution is to look at it through one lens and say that “simple is better”. But is it? If you want the prosperity that comes along with market driven economies, you must deal with its complexities as well. And maybe this just shrewd political posturing by a Chinese President to keep the “masses” believing that class distinction by wealth does not truly exist in China today?

China has become a world power, not because of its Marxist ideology, but because of its market driven economy that has driven its current international wealth and power. Turning back the clock to the simpler days of Marxism is not the answer in a complex world. As this article suggests, the revamping of its underlying social infrastructure/taxation/international market trading is the surest way to continued success. Can simple solutions truly be the answer in today’s world?